Herding Cats Through a Mine Field

EDITORIAL

Every once in awhile I hear someone in the repossession space suggesting that the industry should launch a strike for higher fees. On the surface, it seems like a good idea, but there are some major obstacles to this, namely the law.

Auto loan delinquencies are high, especially in the subprime auto market. Repossession volume is at a peak with no end in sight. If there was ever a time in the past fifteen years that lenders need a strong repossession industry it is now.

So why are lenders and forwarders still paying basically the same, or less, than they did over twenty years ago? Simple, because there is no pressure to make them pay more.

So, why don’t the repossession associations, or at least a determined and large group of agency owners strike and demand that agents get paid a fair fee? It’s not that simple.

The Associations

As an industry, the repossession agency space is extremely fractured. There are two national associations, the Eagle Group XX and sixteen state associations.

Neither the American Recovery Association (ARA) nor the Allied Finance Adjusters (AFA) are labor unions or traditional employee organizations; they are trade associations representing independent repossession agencies and recovery professionals.

While the actual size of the repossession industry cannot be verified, most data points to there being at least 1,700 companies across the nation who conduct more than ten repossessions a year.

Of these 1,700 companies, perhaps 600 are members of any association. As a result, a very large population of the industry would be unlikely to participate in an association endorsed strike or boycott.

Even worse, as has happened with prior unity attempts over the decades, this industry has always had owners who quickly turn on their fellow agency owners either out of fear of future reprisal or believing that they can acquire a larger bulk of business. Even if someone did manage to get a big enough group together, any attempt to lead a large strike would be like trying to herd cats through a minefield.

In other words, maintaining discipline and unity would be difficult with agency owners, who are a pretty independent bunch, maintaining unity for very long would be difficult to say the least.

The only possible way to get enough agency owners to strike would require one or more associations combined efforts. So, even if they can’t orchestrate a strike, why don’t the repossession associations just come out and set what they believe are industry standard fair fees?

The 1981 DOJ Action

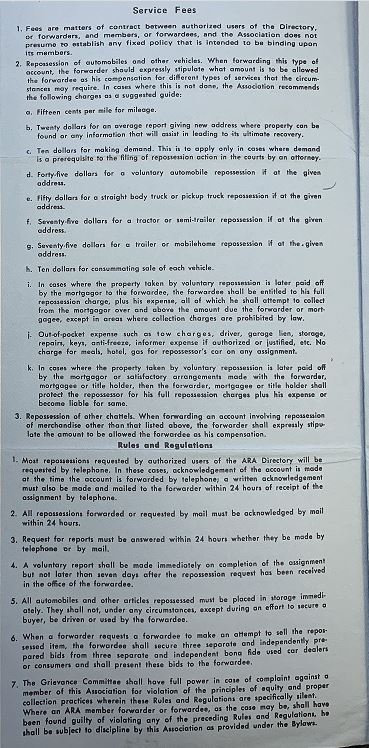

While the repossession industry has never launched an all out and united strike. When they were at the peak of their strength, it wasn’t needed. Membership held greater value by an agencies placement in the association directory, sometimes referred to as “the book.” Back in the days before the internet and forwarders, “the book” separated the repo industries major players from the smaller companies on the sideline scrambling for clients.

Being in that book and being a member of an association was contingent to keeping in line with the association leadership. And that leadership kept a pretty good grip on “suggested” repossession fees.When I say “suggested”, I mean that’s what the books literally said. In reality, if an agency owner was found completely outside of these “suggested” fees, they could lose their membership or lose any value in it and find their phone numbers entered wrong and cause them to lose any response to their listing.

But since association members had guaranteed territories without competition, those left out created new associations until there were four national repossession associations. And once they appeared pretty set, along came a disruptor, a New Mexico agency owner who was denied entry into all four and his complaint made it all the way to DC.

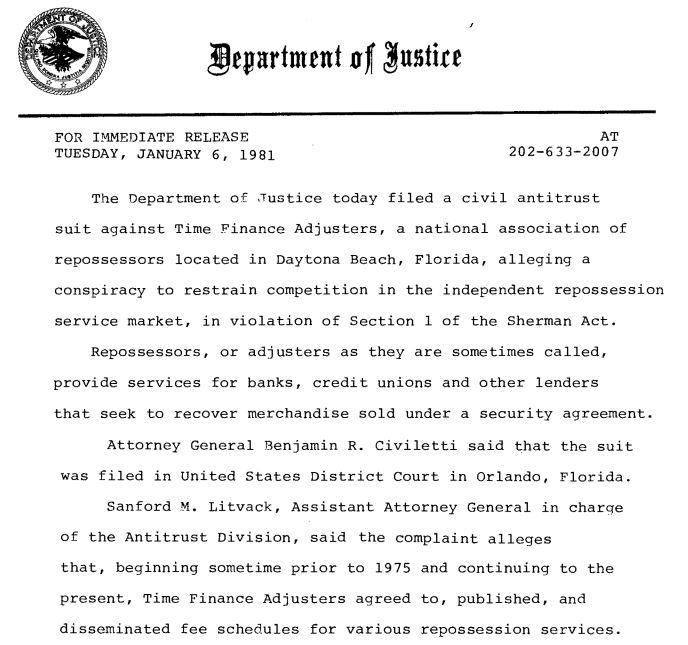

On January 5, 1981, the then National Finance Adjusters(NFA), Time Finance Adjusters (TFA), ARA and AFA were served papers by the Antitrust Division of the Department of Justice. The charges against them were, conspiracy to fix prices, restrict territories and limit membership in violation of the Sherman Act, 15 USC.

Without an admission of guilt, the NFA and AFA and TFA settled without court trial. Reportedly, all of the associations except the ARA paid a fine of about $25,000. The agreed upon terms of the settlements were massive and sweeping.

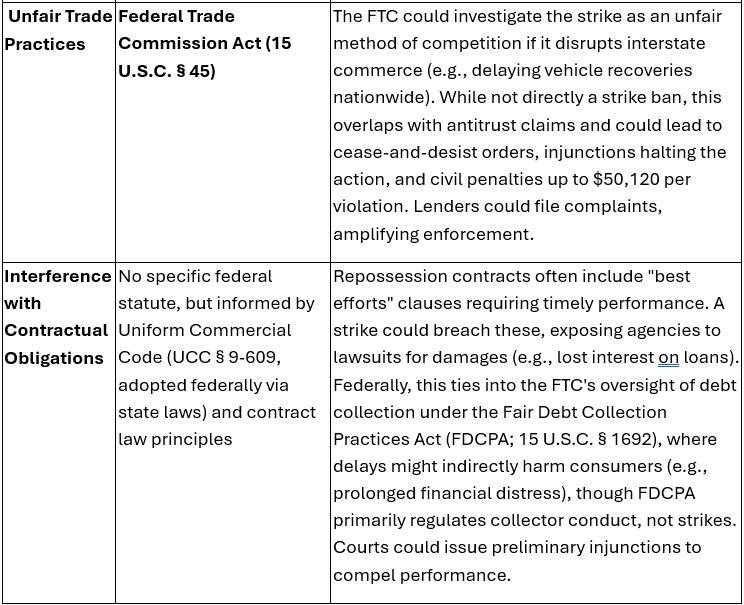

Prohibited Conduct

Under Section IV of the proposed Final Judgment the defendant is restrained from

( l) fixing any price schedule or list for repossession services;

(2) advertising any price schedule or list for repossession services;

( 3) publishing any price schedule or list for repossession services:

( 4) participating in any communications with representatives of other repossessor associations that relate to any price schedule or list for repossession services; or

(5) engaging in any conduct the effect of which is to influence the formulation of any price schedule or list for repossession services.

Numbers (4) and (5) utterly neutered the associations control of fees. After a three-year fight, the last association settled. After that, the associations lost the opportunity to even discuss what a best practice in pricing looked like. This industry has been hamstrung by this settlement ever since.

In the aftermath of these agreements, life went on for the associations. But the ramifications of their agreements, left the industry out of control of its own destiny and in an “every man for himself” posture with consequences that resonate to this day. Fast forward and the technology, which made leaps and bounds in the 80’s, would eventually assist in exploiting this vulnerability. The 80’s were what could probably be marked as the end of the “Golden Age of the Repossession Industry,”

The race to the bottom had begun.

Remember, this action happened because one disgruntled agency owner couldn’t get listed in any of the association books. What do you think it would look like if a large national bank or even a forwarding company went to the Department of Justice over a cessation of repossession services or strike that harms them directly or the consumer indirectly financially?

Unionizing or Striking

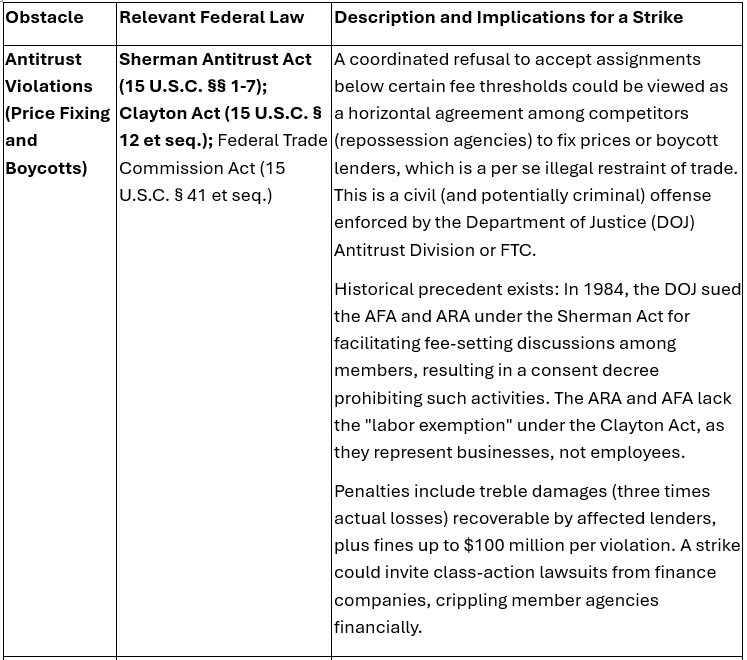

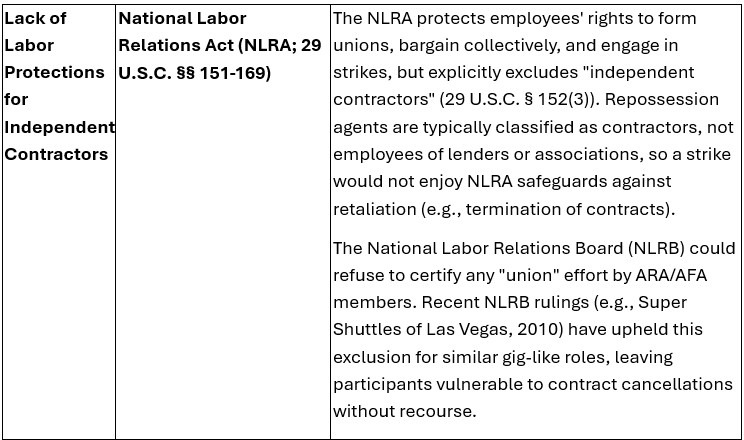

Once again, I must preface that this is not legal advice. If you are looking for legal advice, consult an attorney. As mentioned, aside from the daunting task of getting a large enough majority of the industry to support such an action, there are some legal obstacles to unionizing or striking.

Major Federal Legal Obstacles

Additional Considerations

- Enforcement Risks: The DOJ’s prior 1981 actions against the AFA, ARA, TFA and NFA demonstrated heightened scrutiny of repossession trade groups. A modern strike could prompt swift injunctions under the All Writs Act (28 U.S.C. § 1651), forcing members to resume work.

- Mitigation Strategies: The ARA and AFA could frame the action as non-binding advocacy (e.g., lobbying for legislative fee floors via Congress), avoiding coordination. However, any joint communications urging a boycott would likely fail under antitrust “conscious parallelism” doctrines.

- State-Level Amplifiers: While the query focuses on federal obstacles, states like California (under the Cartwright Act) or New York could pile on parallel claims, but federal preemption often dominates interstate actions.

In summary, the primary hurdles stem from antitrust laws treating a fee-demanding strike as illegal collusion among rivals, without labor law shields. This could result in devastating litigation, making such an action highly inadvisable without restructuring as a true employee union (unlikely given the industry’s model and fractured nature).

Summary

As illustrated, there are many obstacles to a strike aside from the mass and unity necessary. Whether or not the DOJ or other legal action could occur is anyone’s guess, but it is a considerable risk and one that the associations already paid for once and don’t expect them to do it again.

The repossession industry has been struggling with these issues for decades now and there appears to be no simpler solution than the obvious. Everyone needs to know the value of their services and demand them, not just now, but in the future.

While repossession volume is currently at its peak, the individual agencies need to thin the client herd on their own. If a lender or forwarder is underpaying, underperforming or too difficult to work with, it is the agency owner’s professional duty to themselves, their company and their employees to make the decision whether to cut that client.

It is now, while the lenders need the agencies most, that the industry must make these moves. The lenders will only change their price point and practices when they can no longer receive the services they need.

While things may appear rosy for the industry now, the thin profit margins are unsustainable under normal circumstances. If the repossession volume dies down, the leverage will be lost when everyone starts scrambling for assignment volume to pay for all of the new trucks and other expenses they assumed while things were good.

I apologize if I seem to be illuminating the strength of the lenders legal positions and the weaknesses of the repossession industries dysfunctional structure and fractured nature, but it is an inconvenient truth. Remember, we teach people how to treat us. At the end of the day, everyone needs to pick their own fights and that starts with agencies choosing and retaining their clients better and use that simple word “No” more frequently.

Kevin Armstrong

Publisher

More Stories

Colorado Bill Aims to Severely Impact All Repossession Operations

Today is Fallen Agents Day – 2026

From Auction Cutting to Field Programming: The Structural Shift No One Budgeted For

Bad Apples in the Repossession Industry

Why Self-Help Repossession Is Taken for Granted — and Why Losing It Would Hurt Consumers Most

A Necessary Distinction: Financial Oversight vs. Financial Control