During a period in American history that most people lived within walking distance of work, the need for an automobile was limited and the majority of purchases were by the wealthy and for business purposes, but the novelty and “keeping up with the Jones’s” of auto ownership eventually took hold. In 1920, the Federal Reserve issued a memorandum to all banks: “do not offer financing for automobiles used for pleasure.” Such concern was based primarily on a fear that this was just a growing fad and that when it passed, the banks would be put at risk from massive losses. This conservative viewpoint was met with skepticism and opposition in that it created challenges to lenders in determining the difference between a loan applicant using an automobile for business or for pleasure. It went even as far as becoming a constitutional question posed, that the right to automobile ownership was clearly stated in the Declaration of Independence:

“The “pursuit of happiness’ is one of the inalienable right that was woven into the Declaration of Independence and even tho it may appear to some of us that a man engage in this pursuit foolishly, yet so long as he remains within the law, pays his debts, and harms no one, his conduct should be free from the restricted action of the Federal Board and all other Governmental agencies. This is Democracy.” – The Willmar Tribune, July 28, 1920

With this inalienable right, affordable vehicles and access to credit, the American Automobile culture was born. While most Americans still purchased their cars with cash, what followed was a proliferation of auto lending and a shift in the perceptions on lending and usury. Following not far behind it, was the natural affect of consequence for failure to maintain scheduled payments, repossessions.

The auto lending industry, as we know it, originated in 1919 to provide to the growing automobile demand in the aftermath of WWI by an automobile manufacturer in Flint Michigan known as General Motors, established in 1908. General Motors established the “General Motors Acceptance Corporation” (GMAC) with five offices nationwide and a year later, opening an office in Great Britain. Ford begrudgingly followed in 1923 with the Ford Motor Credit Company (FMCC). By 1924, GMAC, now Ally Bank, financed it’s 4 millionth vehicle.

Almost since it’s inception, the act of repossessing automobiles was rife with criminal acts of trespassing, physical acts of violence on both debtor and repossessor and public condemnation of it and the men who performed it quickly followed. The negative image of the repossession industry and the people who performed it was born and resonates with the industry to this day.

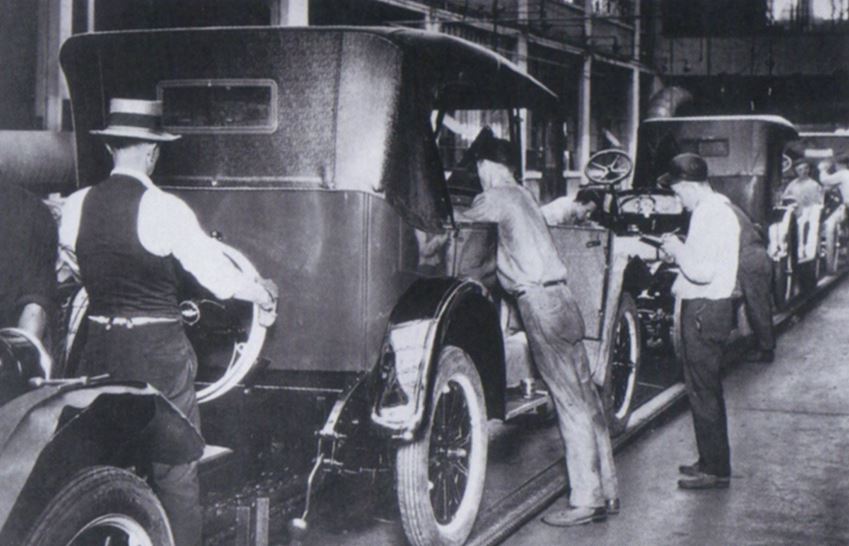

During this era, there were no keyed ignition switches or locking steering wheels built into the mass-produced automobiles. While Bosch had invented the keyed ignition in 1911, they were not in common use. With little more than a pair of switches to engage the common ignition switch, theft security was primarily limited to a crude padlock and chain methods and some forms of crude steering wheel locks, similar to the ones in use today. As the closed canopy model vehicle grew in popularity, the addition of door locks came into common use in 1920. At this time, a pair of bolt cutters and a bendable wire for gaining entry were all that was required to repossess an auto.

It was in 1922 that the name of the first known repossessor is known; “Connie Wembish” founded the “Home Detective Agency” in Greensboro, North Carolina, where they repossessed all types of goods according to Gary Deese, who first worked for and later bought the agency from her in 1966. According to Gary, he learned much of everything he knew about skip-tracing from the agencies in-house skip tracer, HK Williams, who Gary referred to as the greatest skip tracer in the world.

In 1925, William Greenwood of “Greenwoods Garage” at 1150 E. North Ave.,Baltimore, Maryland has the distinction of being the first known and repossession service company.

“Greenwood’s Garage” later transformed into a staple business of the Baltimore area. “Greenwood Towing” and “Greenwood Recovery” are still in operation today and operated in the hands of his grandson, Burton “Buzz” Greenwood.

By 1926, the first documented public outcry against the repossession process was editorialized in “The Evening Independent” of Massillon, Ohio on November 13, 1926, where three men were held in custody of local magistrates for being “Loan Sharks” and charged with demanding usurious interest rates. In these hearings, the first known testimony from an unnamed repossessor, states that he was being paid $25 per vehicle for repossessions. That equates to $365.36 at the time of this writing in 2020 (Kind of funny how anyone would accept less than that now.)

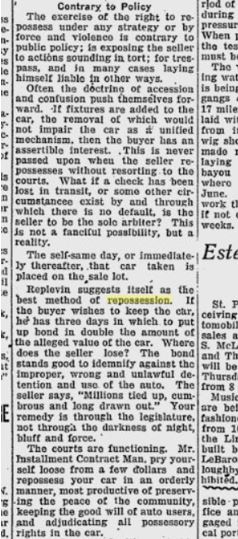

An editorial published on the same day, states; “And my opinion is that the taking of a car on the public streets is not a peaceable repossession. Bloodshed, criminal prosecution, hatred, malice and increased litigation flow from the exercise of force and violence in the clandestine taking from a buyer the car in his possession. To allow the auto dealer to take cars in this manner is to sanction furniture dealers in going into private homes and taking furniture held by the buyer, upon the installment plan.

“Contrary to Policy”

The exercise of the right to repossess under any strategy or by force and violence is contrary to public policy; is exposing the seller to actions sounding in tort; for trespass, and in many cases laying himself liable in other ways. “

While no names or details of the actual tactics employed are detailed, it is worthy to remember that this was during the Prohibition and the rise and proliferation of organized crime across large swaths of America. With these organized criminal enterprises flourishing, loan sharking and the employment of nefarious individuals to collect on these “Shylock” loans soon attached themselves to segments of the repossession process. At the same time, bank and finance company repossession activity was primarily performed by the lenders themselves, private investigators or hired locals with no specific industry affiliation, a recovery process that was maintained clear into the 1990’s with some lenders.

With the new auto lending industry now growing and expanding automobile ownership to most economic classes of Americans, what happened to the lending and repossession industries, as well as the entire American economy, on October 29, 1929, changed America and the world forever. Over the next four days, stock prices crashed 22% over four straight days in what became known as the “Stock Market Crash” of 1929. What followed, was “The Great Depression”, which cost the American economy a 65% drop in foreign trade, 10% deflation, a 65% reduction in home values and the closure of over one-third of the banks in the nation.

Under the 25% unemployment rate, home and farm foreclosures devastated the American Dream of auto ownership, then at 50% of the population owning at least one automobile. With the swell of homelessness across the nation and the mass exodus to find new work all across the country, came a rise in repossessions and skip investigations and loose networks of private investigators and repossession agents cross country to “Forward” the repossession assignments to for a small fee, a practice which persisted in that manner clear into the latter part of the 20th century in an informal and sometimes more formal manner as lenders began maintaining longer term relationships with their repossessors.

As banks began failing and businesses shuttered, auto lending underwriting guidelines tightened and interest rates skyrocketed, essentially killing the auto sales industry. As the auto lending industry plummeted into oblivion, defaults rose dramatically and collateral became increasingly more difficult to repossess. During this era, only 41% of American households owned a telephone and deteriorating financial circumstances led to rising disconnected numbers leaving lenders with often numerous delinquent accounts to visit after banking hours and many miles to travel in their efforts to collect payments or repossess the vehicle. These tactics were inefficient and lenders began reaching to a solid and guaranteed industry for help. The insurance industry.

Insurance adjusters, known for travelling great distances to examine damaged vehicles, began being contacted by lenders to incorporate visits to delinquent borrowers into their runs for a rate of $25 ($386 in 2020 currency) for recovering past due payments or taking the vehicle, which in that era, the public sense of honor was high and they would sometimes even wash it before turning it over. In the depression economy, the census records show that the average monthly income was $1,368 a month. This made the lender visits more lucrative than the insurance adjustment jobs and many “Adjusters” switched over to this new profession while maintaining a portion of their former position title of “Finance Adjuster”. This was the birth of the professional repossession agency and the name “Adjusters” became the common name for repossessors at the time and for decades to come.

February 14, 1929 – Washington DC, one Edward Bishop, an attache on a Naval Air Station, was working part time repossessing a vehicle with a Herbert A. Ridglet for an un-named motor finance company, is the first recorded “Adjuster” shot in the field. Bishop had alerted the borrower, James A. Tatum of the 200 block of Massachusetts st. when he triggered an improvised burglar alarm. Tatum fired on him from the second floor, striking him twice in the hip. Judge Isaac R. Hitt later in March, dismissed the charges of assault with a dangerous weapon and also demanded the lender return the truck to Tatum claiming that the adjusters had no legal right to be on the premises at the time of recovery and that Tatum had a legal right to defend his property. This legal sentiment and borrower response became an industry standard, often repeated through the next ninety years with often deadly results.

NOTE: The book is broken down by decades with the 1930’s giving birth to the “National Association of Allied Finance Adjusters” and Summs Skip and Collections Service’s, who had been operating out of an office in the back office of a bank.

This is an industry carried down from father to son and daughter for generations and now at almost one hundred years of age I feel is worthy of recording before it becomes forgotten. I may or may not publish more of this online. I have been provided some really cool images from the “Golden Age” of the industry (1950’s-1970’s) that I look forward to sharing one way or the other.

Thank you. – Kevin Armstrong

Related Articles:

Repossession history – the 50’s-60’s memoirs of Bill Bowser

On this day in repossession history, 1994 – John Henry Peters murder

The History of Auto Repossession in North America – The 1920’s

The First Repo Man and First Auto Repo in History

February 25th – Fallen Agents Day

The History of Auto Repossession in North America – The 1920’s – The History of Auto Repossession in North America – The 1920’s – The History of Auto Repossession in North America – The 1920’s

More Stories

Colorado Bill Aims to Severely Impact All Repossession Operations

Today is Fallen Agents Day – 2026

From Auction Cutting to Field Programming: The Structural Shift No One Budgeted For

Bad Apples in the Repossession Industry

Why Self-Help Repossession Is Taken for Granted — and Why Losing It Would Hurt Consumers Most

A Necessary Distinction: Financial Oversight vs. Financial Control